Lord Timothy Dexter | The Luckiest Fool in History

Good old/poor old Timothy Dexter: illiterate, peculiar, a local laughing stock, but perhaps the luckiest fool in history.

Funny old life, eh? Truth is stranger than fiction, etc. In one of those curious, is-this-reality-or-is-this-from-the fevered-imagination-of-a-biographer-type scenarios, it turns out that one of America’s first millionaires was also an eccentric who staged his own funeral, mistook his living wife for a ghost, and fancied himself the greatest philosopher in the Western world.

While we may think that the chaotic antics of a multimillionaire are a recent phenomenon (see Bezos’ joyride into space in a phallic-shaped rocket), Timothy Dexter proves that peculiar behaviour has been a hallmark of the super-rich for centuries.

Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. - F. Scott Fitzgerald

Born on January 22, 1747, Timothy Dexter's early years were a prologue that provided little indication of the acts that would unfold. A success story that defied all odds, Dexter had luck on his side, turning a series of seemingly absurd investments into a miraculous fortune. Hailing from humble beginnings in Malden, Massachusetts, Dexter was raised in a poor family and had no education. As a teenager, he toiled away as an apprentice for a leather tanner. After completing his apprenticeship, his employer rewarded him with a new set of clothes known as a freedom suit. Though he had cut his teeth in a respectable trade, he yearned for more and aspired to join the upper classes. In pursuit of his dreams, he sold his freedom suit for eight dollars and twenty cents, using the funds to move to Newburyport —a town that attracted artisans.

As luck would have it, Dexter soon crossed paths with Elizabeth Frothingham, a wealthy widow ten years his senior. Whether it was her charm or wallet that won him over, he courted Frothingham, tied the knot, and moved into her lavish home in Boston's esteemed Charlestown neighbourhood. He set up shop in the basement of his wife's house, selling moosehide trousers, gloves, hides and blubber. However, despite making a handsome sum from his newly founded tannery, Dexter's dreams of being accepted by his wealthy neighbours were dashed. He was seen as less than equal. His lack of education, unconventional behaviour, and the fact that he married into wealth made him an outcast.

Unwilling to accept defeat and determined to prove himself, Dexter embarked on a crusade, flooding governmental offices with countless petitions begging for a chance to participate in public affairs. Eventually, having grown tired of his persistent requests, they begrudgingly created a new position just for him—"Informer of Deer". In this role, Dexter's important duty was to keep track of the local fawn population. The only catch? No deer had actually been seen in the area for nearly two decades.

Shrewd Businessman or Lucky Eccentric?

Good old/poor old Timothy Dexter: illiterate, peculiar, a local laughing stock, but perhaps the luckiest fool in history. Friends and acquaintances, seemingly trying to undermine and financially ruin him, would propose absurd ventures that turned out to be gold mines. His most notable venture involved the purchase of Continental currency, the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the American Revolution. When the currency became obsolete, Dexter bought it for a fraction of its value, anticipating its future return to circulation. And his foresight paid off when the U.S. Constitution allowed the exchange of Continental money for bonds, making Dexter a rich man. His investment prowess didn’t stop there. Unaware of the city’s booming coal trade, Dexter was persuaded to sell coal in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Much to the dismay of his saboteurs, the Newcastle miners were on strike at the time, enabling him to sell his coal at a substantial profit.

Another occasion involved Dexter selling bed warming pans in the West Indies, oblivious to the fact that the islands had a warm climate, rendering the pans useless. Nevertheless, Dexter cleverly adjusted them and marketed them as ladles to the owners of sugar and molasses plantations, commanding a high price.

He struck gold when he sent winter gloves to the tropics, only for them to be snapped up by Portuguese sailors en route to colder climates. And when stray cats took over Newburyport, Dexter rounded them up and shipped them off to the Caribbean, where savvy plantation owners eagerly bought them to keep their warehouses free from vermin. To the astonishment of everyone but Dexter himself, even his most nonsensical ventures were to prove lucrative in the end.

Lords, Lions and Laureates

By this time, Dexter had acquired great wealth. But despite his best efforts and enormous fortune, he remained a perpetual underdog in high society. Eager to please, he spent lavishly and entertained guests nightly.

His opulent mansion boasted minarets and a gilded eagle perched on the roof. The sprawling grounds were adorned with wooden statues of esteemed figures like George Washington and Napoleon. But that wasn't enough for Dexter - he commissioned two statues in his own image, one proudly declaring him the "first in the East, the first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the Western world." He assembled a vast entourage of servants, including a personal fortune teller and a poet laureate—but there was one strict rule—all servants must address him as “Lord Dexter”. In public, any child who called him “Lord Dexter” could expect a quarter and an adult, perhaps dinner and drinks.

While entertaining his muses, Dexter extended his hospitality to a rather unusual guest. Hosting a "beautiful African lion" for a full week in one of his outbuildings, Dexter announced his foreign visitor in the local press as "really worth the contemplation of the curious", adding that the price of admission would be nine pence.

As Dexter's eccentricity grew, so did the distance from his wife, and his treatment of her sank to miserably low levels. He often informed visitors that his still-very-much-alive wife had passed away and that the woman seen in the building was her ghost. Dexter, in his relentless pursuit of acceptance, staged his own death to test the authenticity of his mourners. In his own written account of the faux-funeral, he alleged that a staggering three thousand people turned up to pay their respects and displayed “much criiing (sic)”. However, his wife, who was in on the ruse, failed to mourn to his liking. In a rather dramatic attempt to elicit the desired amount of sorrow, he resorted to some less-than-deal conflict resolution tactics and caned her.

A Pickle for the Knowing Ones

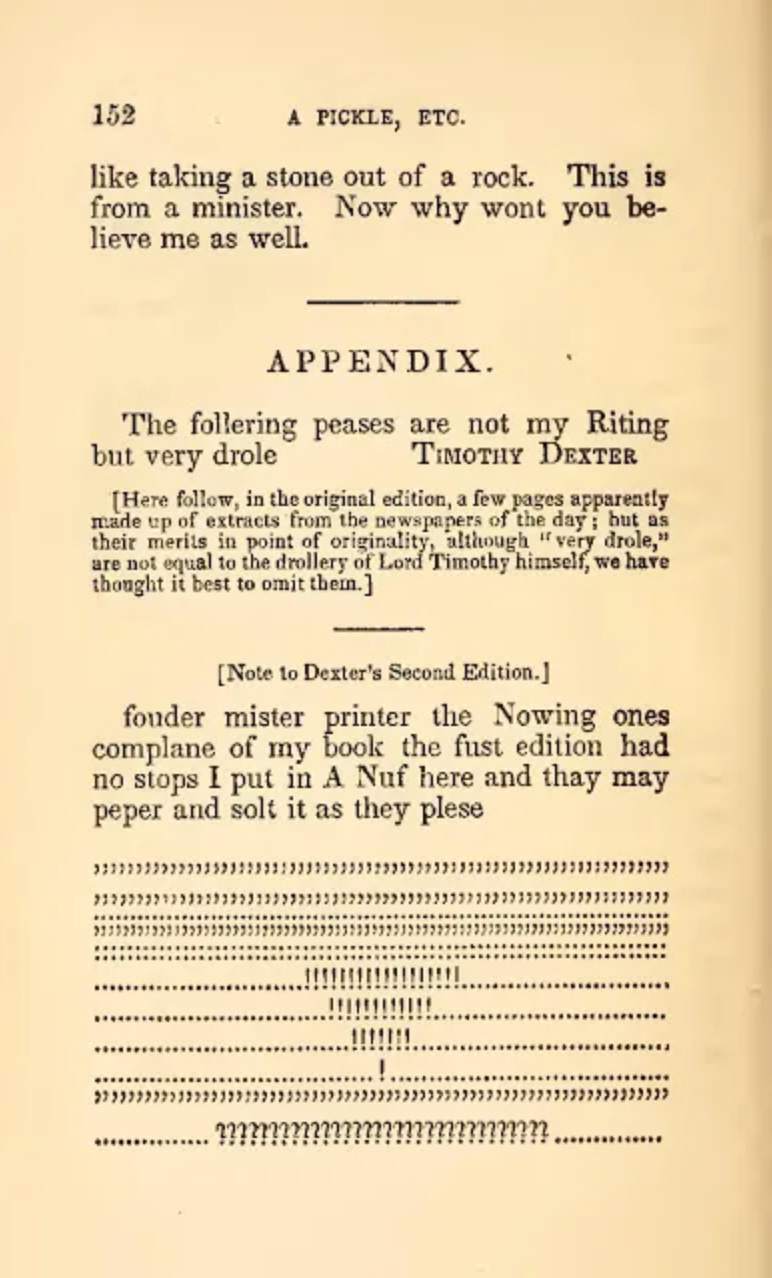

Once nearing the actual end of his life, Timothy Dexter wanted to leave a legacy and a way for future generations to remember him, and so, he penned his memoir, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones. Short, incomprehensible and utterly bizarre, the book criticised the clergy, politicians, and his wife. The work–a collection of correspondence and chronicles—contains no punctuation, numerous misspellings, and random capitalisation. A commenter later described the work as “an egotistical, opinionated, coarse defence of Dexter, by Dexter, against all ‘Enemys’ who were anti-Dexter.”

I was born when grat powers Rouled I was borne in 1747 Janeuarey 22 on this day in the morning A grat snow storme the sines in the seventh house wives mars Came fored Joupeter stud by holding the Candel I was to be one grat man mars got the beth to be onnest man, to Doue good to my felow mortels

The book was handed out for free, and it grew so popular that it went through eight re-printings. However, upon receiving complaints that there was no punctuation, Dexter added a page in the second edition consisting of nothing more than punctuation marks instructing readers could distribute them and that “thay may peper and solt it as they plese”.

Lord Timothy Dexter died at age 59 on Oct. 26, 1806, leaving money for the care of Newburyport’s poor. Following his death in 1806, Newburyport Herald published an obituary stating:

His ruling passion appeared to be popularity, and one would suppose he rather chose to render his name “infamously famous than not famous at all.” His writings stand as a monument of the truth of this remark; for those who have read his “Pickle for the Knowing Ones,” a jumble of letters promiscuously gathered together, find it difficult to determine whether most to laugh at the consummate folly, or despise the vulgarity and profanity of the writer.

To this day, there remains a lingering uncertainty about whether this unconventional philosophical "treatise" is simply a prank being played on literary historians. As such, Dexter achieved what he set out to do and left a remarkable, albeit peculiar, legacy. Truth, as they say, can be stranger than fiction, but it could certainly benefit from the guidance of a skilled editor.

He sounds like my kind of guy!

I love the distribution of extra punctuation.